This is The Athenaeum which was founded in 1824 for gentlemen of a literary or scientific turn of mind.

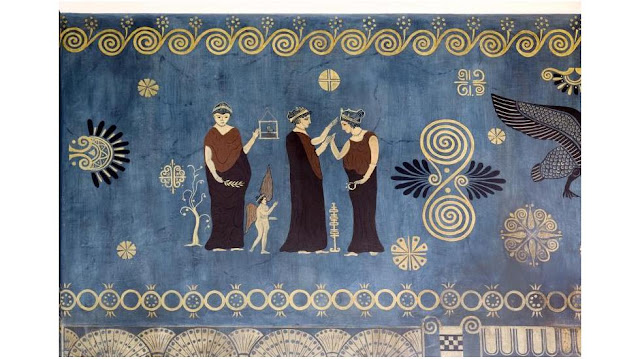

This was built specifically to house the Club, the frieze at the top is a reproduction of the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon in Athens and the gilded statue above the portico is the Greek goddess Pallas Athene.

Famous members have included Charles Dickens, the artist J.M.W.Turner, Charles Darwin and Lewis Carroll.

The Athenæum, which Richard Saul Wurman describes "as unforgetably beautiful" (51), faces what was originally The United Service Club by John Nash and Decimus Burton (1828), which was originally founded for military officers who had fought in the Napoleonic Wars and now houses the Institute of Directors. The Athenæum, as it turns out, also had a relation to Britain's conquest of Napoleon, for as Ian Jenkins of the British Museum, points out

The Athenæum was founded in 1824 as a 'Club for Literary and Scientific men and followers of the Fine arts.' The building rose in 1829-30 as part of the new civic architecture in Greek style by which London was embellished after the battle of Waterloo. Following the defeat of Napoloneon, whose ambition was to transfer Rome to Paris, Britannia Victrix had sought a different model from Antiquity by which to shape her capital city. She found it in the democratic society of Periclean Athens. On the balcony over the porch of the Athenæum, Pallas Athena — a close replica by E. H. Baily of the Athena Belletri — was set up to preside over Waterloo Place. She was the warrior goddess of wisdom and patron deity of ancient Athens. [p. 149] Inside, on the staircase, a copy of the Apollo Belvedere, commander of the nine muses, stands watch over this modern museion. In niches of the flank walks of the entrance hall were casts of two statues then as now, in the Louvre, the so-called Venus Genetrix and the Diane de Gabies.

Past members include Joseph Conrad, Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens, W. Holman Hunt, Thomas Huxley, Rudyard Kipling, Lord Leighton, John Ruskin, and many members of the Anglican clergy.

Joseph Hatton's Clubland (1890) on the Athenæum

"The Athenæum is the chief literary club of the metropolis. It is built upon part of the old courtyard of Carlton House. The architecture is of the Grecian order, severe and impressive. The frieze is copied from that of the Parthenon. It was the colossal figure of Minerva over the Roman Doric portico that inspired the epigram : —

"Ye travellers who pass by, just stop and behold,

And see, don't you think it a sin,

That Minerva herself is left out in the cold,

While her owls are all gorging within.

"The figure is by Bailey, and is a fine example of his art. The hall is divided by scagliola columns and pilasters, the capitals being copied from the Choragic monument of Lysicrates. In this "exchange or lounge " (to (quote Timbs), "where the members meet," there are two fire-places; " over each of them, in a niche, is a statue — the 'Diana Robing' and the 'Venus Victrix,' selected by Sir Thomas Lawrence — a very fine contrivance for sculptural display." In the library hangs Sir Thomas's last work. It is a portrait of George IV. He was engaged upon it a few hours before he died. Among the many fine busts in the various rooms is Rysbach's Pope, and a fine study of Milton, presented by Anthony Trollope. Although the revival of Gothic architecture is just now a national sentiment, and is in keeping with the exigencies of our climate, one finds, in the best features of Grecian and Italian Art, much that is noble and elevating even under our grey and unsympathetic skies. The design of the Athenæum is a help to the dignity and repose which is characteristic not only of the exterior, but of the rooms in the house itself. If the members have collected a library that is said to be the best of its kind in London, the architect and decorator, repeating classic models, have enshrined the volumes with characteristic taste. It brings the admirer of all this sadly down to the realism of the outer street when one is told that a member, desirous to refer to the Fathers on a theological point, asked one of the officials if "Justin Martyr" was in the library, and was answered, "I don't think he's a member, sir, but I will refer to the list." [27-29]

The Plaster Busts at the Athenæum

There are ten bookcases in the Drawing Room at the Athenæum; on each of them there is a portrait bust of a distinguished man. The busts are life-size, made of plaster. Every man was pre-eminent in his respective professions and thus the room becomes a kind of Pantheon, or ‘Temple of Worthies’ representing a wide range of different arts and sciences.

The list below runs clockwise from the central fireplace. With each person is given his respective métier:

William Shakespeare

John Locke

Sir Isaac Newton

David Garrick

William Harvey

John Milton

Dr. Samuel Johnson

1st Earl of Mansfield

Sir Joshua Reynolds drama

philosophy

natural science

poetry, historical romance

acting

medicine

letters, lexicography

jusrisprudence

painting

The busts, with one exception, were made in 1830, but they were not in their present places before 1920, so the tidy arrangement we have today is not the original. Moreover, in this company Walter Scott is a stranger. He was a foundation Member of the Club and died in 1832, but his plaster portrait, which was was made later than the rest, it is not recorded at the Club until 1898. . The others were made in February 1830 by P Sarti of Dean Street, Soho, who was one of the most active of many plaster casters then working in London. Sarti’s account survives in the Club’s Archive, and from it we know that he supplied three more busts (which have been lLost), viz:

Sir Francis Bacon

Alexander Pope

Sir Christopher Wren philosophy

poetry

architecture

However, the full complement of busts at the Club, according to a Committee minute of 1833, also included:

Edmund Burke

John Flaxman statesmanship

sculpture

In 1833, there were fourteen busts, of which four – Bacon, Flaxman, Pope and Wren – have been lost. The bust of Burke was presented in January 1830, by the nephew of the sitter. However, it seems that in 1920 Burke was not considered appropriate for the vacant place among the Worthies, which was given to Sir Walter Scott.

No record has been found of any Committee choosing the portraits; it this must have taken place during the winter of 1829-30, when the interior of the Clubhouse was nearing completion. Who made the choice? Again there is no record, but the five Trustees made up a strong intellectual group. . The ubiquitous John Wilson Croker combined political activity with studies of history and art; Davies Gilbert was a botanist and geologist; the Earl of Aberdeen, philhellene scholar, was at the time Foreign Secretary and a future Prime Minister; Lord Farnborough was an acknowledged connoisseur of art and adviser to the King at Windsor Castle.

The fifth Trustee was the painter Sir Thomas Lawrence, President of the Royal Academy, and himself a collector of drawings. Among the Members, the sculptor Francis Chantrey, who was on a sub-committee, made ‘frequent suggestions for the decoration and internal arrangements’ (Tait p.19).

The Club had apparently decided against hanging oil paintings, and was already buying plaster statues for the Hall and Staircase (Tait pp. xix-xxii). It seems likely that the plaster busts were ordered specially to furnish the Drawing Room, and were carefully chosen for a Club dedicated to literature, the arts and science. . Letter Letters and poetry may seem a little over-represented, but the purpose, clearly, was to reflect a broad range of intellectual achievement in liberal and fine arts. . However, the fourteen plaster portraits appear to have been collected without any particular plan as to their placing.

Another interesting point is that these plaster casts were readily available. The process of making plaster casts is described later. Evidently, in 1830, a range of subjects such as these could be chosen without difficulty; Sarti will have had ready to hand a good collection of the moulds required. All the original plaster busts, including Burke, appear to be of the same manufacture, i.e. from Sarti’s own workshop. Each one rests on a name-tablet or label, which is a narrow horizontal fillet 1 inches high, with a scroll at each end. This feature was taken from ancient Roman busts., and From about 1740 the name-tablet was the fashion at Rome with sculptors and restorers like Cavaceppi and Albacini, and it was used in England by classically minded sculptors like Nollekens and Banks. However, after 1790 it was going out of fashion and is rarely found in the 19th century (though it appears on the Club’s marble bust of J .W. Croker). Sarti charged for ‘painting the names’ on the busts, but the busts have been overpainted in white gloss and the letters have been obscured. The names are now written on rather intrusive pieces of gilded wood which are firmly affixed and cannot safely be removed.

Each bust will also have stood on a circular base, or socle, nearly four inches high, which was of plaster and cast integrally with the name-tablet. An inventory dated 1939 describes the busts as being twenty-eight inches high, which indicates that then they were still on socles; without the socles, their average height is more or less twenty-four inches. The brutal removal of the socles therefore probably dates from after the 1939-45 War, and the gilded name plaques perhaps from the same period.

The bust of Burke, however, survives in its original state. As we have seen, the Club possessed it some days before the others. Sarti supplied for it a ‘pedestal’, or socle, to make it uniform with the rest. Burke’s socle has survived, with the inscription ‘BURKE’ in black paint, and it may well be the original white paint that remains on the surface. The hollowed back has the same character as the other busts, i.e. rough, showing how the wet plaster had fallen into the mould.

In this last particular the bust of Walter Scott is different, in that the hollowed back has been smoothed down. This indicates a later period and style of casting.

Sarti dated his bill 3rd February 1830, but two of the busts (Reynolds and Wren) were, we know, ordered a few weeks later. From the way Sarti has set out his account (Appendix I), it looks as though the Committee ordered the first nine busts on the list a bit rather earlier than 4th February 1830. A Committee minute tells us that the busts of Reynolds and Wren were ordered on 23 February (Appendix II); that of Garrick, who was less intellectual than the others, looks on Sarti’s bill looks like an afterthought. That leaves one unrecorded bust, that of the sculptor John Flaxman. Almost certainly this was a cast of the marble bust by E .H. Baily, which belonged to Sir Thomas Lawrence.

There is curiously little information in the Committee minutes, but it seems that very early on six of the dwarf cabinets shown in Decimus Burton’s approved drawings of 1829 (Tait, Pl. XX) were replaced by bookcases: four were on the east wall, and two flanked the South Library door. In 1833, two more bookcases were erected to stand either side of the Map Room (now the North Library). A Committee minute of 7 May 1833 gives in detail the arrangement of the fourteen busts round the room:

Book Cases near the Library

Bookcases near the Map Room

Brackets on each side the Centre Glass

On the Mantel Pieces at the end of the Room

Centre Pope — Locke

Johnson – Burke

Reynolds – Wren

Bacon - Newton

Shakespeare — Milton — Garrick — Harvey — Mansfield — Flaxman

So eight ‘Worthies’ were placed on eight bookcases, and the other six stood on brackets and chimneypieces. Most of the busts were grouped by pairs, Reynolds and with Wren, Shakespeare with Milton; but the four listed above in the bottom line did not ‘mate’ so readily, and were put on the bookcases on the east wall. The Club evidently owned more busts than it had places, and the result, using the mantelpieces, was not very orderly. Observe that in 1833 the named busts included Burke, but not Walter Scott.

This 1833 arrangement can be seen in the Club’s oil painting of 1836 by James Holland (Tait, Pl. XXI). The bookcases were about eight feet high, which is three feet less than today, and the busts will have loomed larger than they do now. This point is not unimportant because the casts are of high quality and had been made from well-known original portraits by distinguished sculptors. As they now stand, however, they look well enough from the floor.

Nineteenth-century Arrangement of the Busts

By the end of 1836 the ninth and tenth bookcases had been made, to stand either side of the central fireplace where previously Reynolds and Wren had stood on brackets. An Inventory of 1838 says there were sixteen busts (which were not named) in the Drawing Room, but that is hard to account for; only fourteen are documented, and no others seem to have been received by that time. Then, in 1845 the bookcases were all rebuilt as they remain today, i.e. nearly eleven feet high, by the cabinet maker William Holland and Sons of Marylebone Road (Holland later moved to Mount Street, and he compiled the Club’s 1866 Inventory).

About the same time, most of the busts were taken downstairs. Six wall brackets were put up in the Entrance Hall, one either side of each fireplace, and two on the west wall. In 1846 the bas-reliefs by Thorvaldsen of Morning and Night were ‘placed over the false doors right & left of the Stair-case’; those false doors have since been removed). The brackets were for Milton, Newton, Bacon, Wren, Shakespeare and Reynolds. Four more brackets in the Morning Room held Johnson, ‘Dryden’ (obviously an error for Locke), Pope and (presumably) Burke. The list omits Garrick, Harvey, Mansfield and Flaxman, which will have remained on the east wall of the Drawing Room.

The busts are mentioned in subsequent inventories, which give the number and location of busts, but not again by names until 1894. In 1856 there were twelve busts on brackets in the Staircase Hall and Morning Room, and none in the Drawing Room, so two appear to have been lost. Two more were missing in 1866, when there were four busts in the Morning Room and six in the ‘Lobby and Corridor’.

The ‘Lobby and Corridor’ were in the basement. By 1894 all the other plaster busts had joined the party in the basement, and there they remained for twenty-five years. In 1920 they were taken upstairs and put on top of the bookcases: all, that is, except Burke who remained down below. The movements are described in a scholarly 1939 Inventory compiled by H. Clifford Smith (see Appendix IV). At least, Smith gives the date as 1920; but in the photograph of the Drawing Room published in Humphry Ward’s History of the Athenaeum (1925), no busts are to be seen.

It seems that after 1866 plaster busts had no real place in the Club; indeed they may have been seen as a bit of an embarrassment. Yet somehow they survived, and in good condition too. Any damage seems to have happened after 1920, namely a coat of white gloss paint; the removal of socles and the imposition of gilded name labels (except on the bust of Burke).

The present placing of the ten busts, both as decoration and as iconic symbols of esteem, seems so logical that in retrospect it’s hard to understand why it took so long to achieve. They stand on the bookcases exactly like library busts, which by a long tradition were placed on the tops of shelves in college and private libraries.

The Tradition of Library Busts

In the seventeenth century it was already common practice to put busts of authors on the tops of library bookcases. Normally the portraits were of ancient writers, i.e. classical poets and philosophers, but by the eighteenth century they would also include modern authors. The busts might be of marble or plaster.

In Britain, three great libraries of the mid-eighteenth century had series of portrait busts, which are described by Malcolm Baker in his study of the Wren Library. At Trinity College, Dublin, marble busts of twelve literary figures, ancient and modern, and two benefactors were supplied in the 1740s; six were by Roubiliac and eight by Scheemakers. The two other libraries, which we shall describe in greater detail, are the Codrington Library at All Souls’, Oxford, and the Wren Library at Trinty College, Cambridge. All the plaster busts at Oxford, and probably all those at Cambridge, were made by John Cheere (1709-1787).

John was a younger brother of the distinguished sculptor Sir Henry Cheere. He worked principally in modelling and casting sculpture in plaster and lead, and was without doubt the most active of several eighteenth-century craftsmen in these media. As well as making statues and statuettes, John Cheere specialised in portrait heads both ancient and modern, which he supplied either at life-size or reduced. His works in plaster and lead are to be seen in several country houses today.

At All Souls, Oxford, the Codrington Library has twenty-four plaster busts of eminent fellows of the college. They were modelled and cast in the years 1749-1752 by John Cheere, who evidently based them on paintings or engraved portraits. The bust of Wren, for instance, has no resemblance to the famous marble by Edward Pearce in the Ashmolean Museum, but came presumably from an oil portrait or engraving. The busts are placed on the shelves, high above floor level. Originally they were white, but at some point they were painted black with the result that the features now are scarcely recognisable from below. The College had decided on these twenty-four busts: however, they may not have been thought completely successful because, except in one instance, the sculptor is not known to have repeated any of them. John Cheere’s later and more typical works are based on well-known ancient marbles or modern portraits by famous sculptors. .

At the Wren Library, Cambridge, above the shelves there are twenty-four plaster portraits of classical and modern English authors. No documentary evidence has been found to prove Cheere’s authorship, but it seems to have been he who modelled and supplied them, though perhaps he had some outside assistance. The college had made out their list of the authors before 1753, and the busts were in place by 1763. The original sources of the portraits are not always clear; however, most of the ancients are based on well-known classical busts (but no sources are known for Cheere’s Plato and Horace). The modern authors were based on historical busts by different sculptors: Pope, for instance, on a famous bust by Roubiliac, Milton from Rysbrack maybe, and Locke from an engraving by Vertue. All these works, we may assume, were modelled or remodelled, at life-size, by John Cheere. The Shakespeare, Milton and Locke busts are typical instances of the ‘John Cheere’ style of modelling. They are competent portraits, but they have neither the rococo elegance of his brother Sir Henry, nor the baroque gravity of Rysbrack.

In addition to the plaster busts in the Wren Library, at floor level there are fifteen fine marble busts of eminent members of the College. Ten, including Newton and Bacon, are by Roubiliac, four are by Scheemakers, and one (later) bust is by John Bacon.

Four of the Athenæum busts (Shakespeare, Milton, Locke and Newton) and probably two of those missing (Pope and Bacon) were identical to those at Cambridge. It seems that the moulds for plaster casts owned by Cheere were passed down to Sarti, who was able to use them in 1830.

The Athenæum busts represent a wider range of subjects than merely literature. Their scope suggests an analogy with the Temple of British Worthies at Stowe, which contains sixteen historical busts celebrating British achievements in the arts and liberal politics. They were made in stone by Rysbrack and Scheemakers, during the 1730s; six of them are of the same subjects as the Athenæum collection; the others are mostly defenders of British liberties. Rysbrack also supplied sets of historical busts, usually in terracotta, to certain patrons, including Queen Caroline, for Richmond and St James’s Palaces, and Sir Edward Littleton of Teddesley in Staffordshire. Rysbrack often based his models on engravings by George Vertue.

The original sculptors of the Athenæum busts included Roubiliac (Newton), Scheemakers (Harvey), Nollekens (Johnson and Mansfield) and Ceracchi (Reynolds). Apart from the later inclusion of Chantrey’s Scott, the only 19th century ‘Worthy’ was Flaxman, whose portrait was almost certainly a bust by E .H. Baily. By the time the busts were set up they were all ‘historic’, i.e. images of men who were dead; but seven out of the fourteen had been modelled ad vivum, and the seven subjects, then very much alive, had sat for their portraits.

The lost bust of Wren is mysterious. In February 1823, the Committee obtained permission from the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s for Sarti to take a cast from their bust of the architect. But evidently the Club then somehow obtained an existing plaster bust which they passed to Sarti for repair. There is, moreover, no record of St Paul’s Chapter having owned a portrait bust of Wren, though they now own a plaster cast of the famous bust at Oxford attributed to Edward Pearce.

There are several points of interest in Sarti’s bill (Appendix I). One is the relative cheapness of plaster casts: he supplied them for £1. 10s. each. Evidently he already possessed most of the moulds for making the casts, and we have suggested that he had acquired a collection of them from the studio of John Cheere, which had been finally dismantled in 1812. The two exceptions are the bust of Wren (which is lost), and that of Reynolds for which Sarti’s charge of 3 three guineas included the making of a new mould and adding portions of drapery. Another interesting detail is that the Royal Academy would not allow Sarti to keep the moulds of their Reynolds, from which he would have been able to make further casts.

Collections of Plaster Busts

West Wycombe Park, Buckinghamshire. Four excellent ‘bronzed’ (i.e. black) busts are in the Music Room. Milton and Locke are the same models as those in the Wren Library, and at the Athenaeum. The third is Newton, cast from a marble bust but not the same as at the Athenaeum: it is by Rysbrack, not Roubiliac. The fourth bust is of Dryden (after Scheemakers); the same is in the Wren Library, but it is not at the Athenaeum. The busts are full size, and have name-labels (not inscribed) between socle and bust. Placed in the spacious Music Room, these plaster busts have acquired an almost architectural importance. They are first listed in a house inventory of 1782, and were almost certainly supplied by John Cheere in the 1770s. Their splendid pedestals of inlaid marble, as well as the fine marble doorcases and chimneypieces at the house, are likely to have been made by Sir Henry Cheere, elder brother of John. It is curious that the names of neither John nor Henry Cheere appears in the West Wycombe archives.

Shardeloes, Buckinghamshire. There were full-size library busts, circa 1770, of Shakespeare, Milton, Locke, Newton and Pope. Apparently ‘bronzed’, they were bought in 1959 by the City Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, to be shown at Aston Hall. (At present they are in store and not available for inspection.) The socle on Pope is of a type supplied by John Cheere (Baker, Wren Library, fig. 66).

Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire. The National Trust owns full-size plaster busts of Locke (white plaster), Milton and Dryden (both ‘bronzed’), and Pope (‘bronzed’, but a different model from that at the Wren Library). All four have the impressed signature ‘P. Sarti Dean Street, Soho’. They may originally have been at Wimpole, but are more likely to have been acquired as a job lot after 1936 by Captain George and Elsie Bambridge, who owned and refurnished the house.

The Garrick Club, London. White plasters of Shakespeare and Garrick were separately given to the Club between 1834 and 1841. Shakespeare is the same as the Athenæum bust; but it bears the stamp of Robert Shout (c1760-1843), and is thought to date from about 1808. Garrick too is the same as the Athenæum’s example, except that three buttons have been removed from his coat.

The Royal Academy, Burlington House, London. . The Ooctagonal Rroom was constructed in 1867-69, and eight plaster busts, placed high up in circular niches, represent the arts. Four are of Italians (Leonardo, Michaelangelo, Raphael and Titian); and four of English artists: Reynolds, after Ceracchi; Wren, after Pearce; Flaxman, after Baily; and and one of unknown identity.

Making Plaster Casts

Casting in plaster was a normal part of the sculptor’s trade. In The London Tradesman (1747, by R. Campbell), the work of casting is described as ‘merely mechanical’. However it was laborious, and required experienced and professional craftsmen.

A cast can be made from a work in almost any material, i.e. of marble, bronze, lead, wood, clay, terracotta, wax , or another plaster,; and the resulting cast may be in plaster, lead, bronze or other metal. The process is not easy fully to understand if one has not practised it. What follows describes the simplest of various processes.

First, some oil is applied to protect the original; then the object is given a very thick covering of talc or plaster, which solidifies and becomes the mould. For a bust with simple contours the mould might be made in two pieces, forming front and back; but if the hair or drapery is complicated,, and for statues, it will be a ‘piece mould’ consisting of a number — sometimes a considerable number - of separate pieces. The limbs of a statue were often cast separately.

he moulds are then bound together, and liquid gesso (plaster of Paris) is poured into the open base or back. Plaster solidifies quite quickly; when it is quite dry, the moulds are removed. The emerging bust or figure, which is hollow, is then ‘repaired’: the limbs are assembled as necessary; defects and cavities are filled and smoothed. The features can be sharpened up with a chisel. Finally, the surface is given a finish such as lime-wash or paint. Two plaster busts by Nollekens at Castle Howard are of a pleasing blue-grey colour. John Cheere invented the process known as ‘bronzing’ with shellac, which gives an attractive black surface.

After about 1770, the normal procedure of a sculptor, whether of busts or figures, would be as follows. After he had modelled his statue or portrait bust in clay full-size, he would make from it a cast in plaster. The plaster cast was his working model; it was this that would be exactly copied in marble. The advantage of plaster over clay or terracotta was that it would not shatter, distort or shrink when drying. The sculptor normally kept the moulds from which further casts could be made; but he could readily make new moulds if and when they were needed, from the model or finished marble.

Rysbrack, in 1758, sent terracotta models of his busts for casting to Peter Vanina, a professional plaster man. For a bust, new moulds cost three guineas, and each plaster cast sixteen shillings. Vanina wrote that ‘the Mould when Made will be good to cast fifteen or twenty Casts out of it’. Dr Johnson wrote that Nollekens, in 1778, would charge one or two guineas for a plaster cast; but (according to J.T. Smith) he sold plaster casts of his bust of Pitt (1806) for six guineas each. In 1806, Nollekens charged Charles Burney junior £30, which covered making the mould of his father’s bust and supplying twelve plaster casts. By comparison with Nollekens, Sarti’s charge of £1 .10s. for each bust seems moderate. However, plaster busts were sold even more cheaply than that to the Crystal Palace in 1853; a number of them ordered from the British Museum could cost as little as 15s. each.

Plaster busts used to be more common than they are now. They are easily damaged; the cheap material, unless covered by an improving paint or wash, can be unattractive, becoming dirty or dusty. Plaster busts came to be disregarded and were often thrown away. But at certain houses, for example Castle Howard and Badminton, there are still good portraits in plaster by Nollekens, and they look very much at home on the library shelves.

The Athenæum Club's Sculpture

A Temple of British Worthies: The Historic Portrait Busts in the Athenæum

A Catalogue of the Plaster Busts at the Athenæum

Other busts the Athenæum

Athena by E. H. Baily

The Belvedere Apollo

Lord Leighton by Thomas Brock

Psyche by Thorvaldsen

The Athenæum Club's Paintings, Drawings, and Graphic Works

Charles Darwin, replica of painting by Sir John Everett Millais

F. T. Palgrave by George James Howard (drawing)

Cardinal Manning by Alphonse Legros (drawing)

The Peacock's Feather by Robert Anning Bell (watercolor)

Self-portrait, replica by William Holman Hunt of the painting in the Uffizi (painting)

G. F. Watts by Alphonse Legros (drawing)

Members of the Athenæum, a caricature by Burne-Jones (drawing)

References

Bradley, Simon, and Nikolaus Pevsner. London 6: Westminster. “The Buildings of England.” New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003.

Hatton, Joseph. Clubland London and Provincial. London: J. S. Vertie, 1890. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 29 February 2012.

Tait, Hugh, and Richard Walker with contributions by Sarah Dodgson, Ian Jenkins, and Ralph Pinder-Wilson. The Athenæum Collection. London: The Athenæum, 2000. [This volume may be ordered from the Librarian, The Athenæum, Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5 ER.]